Scientific Skepticism 101

Definitions

Pseudoscience = Statements, beliefs, or practices that are claimed to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method

Scientific skepticism = The application of skeptical philosophy, critical thinking skills and knowledge of science and its methods to empirical claims

Logical fallacy = A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning, or "wrong moves" in the construction of an argument

Cognitive bias = A systematic error in thinking that affects the decisions and judgments that people make

Scientific Skepticism

How do we know what’s really real? We tend to view the world through what we believe is an objective lens, that what we see is accurate, consistent and reliable, but the truth is we all have inbuilt biases that make us see our own version of reality - The first part of scientific skepticism is knowing that everyone has these flaws, and how not to let them get the best of you.

Skepticism isn't being cynical and close-minded about things, quite the opposite - It's being able and willing to change your mind when presented with legitimate evidence. Critical thinking is at the core of skepticism, and equally important is understanding the scientific method, being able to assess a claim, weight the evidence and make a judgement based on that. Not all skeptics are scientists, but all good scientists should be skeptics.

Conflicting ideas

If you’ve ever been told you’re wrong about something you may be familiar with the feelings that can accompany that: Feeling defensive, offended and possibly even angry at the person saying that you’re incorrect. This feeling is cognitive dissonance, when we hold two competing ideas in our mind it creates a feeling of mental discomfort. Cognitive dissonance can be thought of as a sort of belief homeostasis; we want our attitudes and behaviours to be internally and externally consistent, and if they’re not we feel uncomfortable (example is a smoker knowing that smoking causes lung cancer but they continue to smoke). There is a reason it can be so easy to react with our emotions, it’s what psychologists call our 'default mode', the mental pathway of least resistance, our knee jerk reaction to things is to respond to them with our emotions, but the reality is our emotions can be easily biased and that makes them unreliable.

It’s important to note that there isn’t anything inherently wrong about cognitive dissonance, it can be a good indicator of what our prior beliefs are, and a signal that we may need to re-evaluate them.

Being able to change your mind (when presented with compelling evidence) is a key part of being a good skeptic, but it often doesn’t come naturally, it's a learnt skill, and being shown we're incorrect is often painful for our ego. Like any skill, if you are open to changing your mind (when given valid evidence) over time your emotions start to lose some of their grip, and you can look at things more rationally.

Our fallible minds

It can be easy to think about our view of the world as accurate; what you see is what you get, but the truth is we don’t view the world objectively, we have numerous biases, both innate and learnt that constantly skew our perception. While in caveman days mistaking a bush in the dark to be a lion (a false positive) may have once been a harmless mistake, it paid to be overcautious rather than the opposite and mistaking a bush for a lion (false negative). These same biases we developed in our cavemen day still reside in us today, the issue is that these formerly adaptive biases are less helpful in modern day where we don’t need many of them to survive, and many actually can be detrimental to us.

It’s important to understand how unreliable our perceptions can be; otherwise, we fall prone to believing our view of reality is objective and irrefutable when it’s quite the opposite.

An unreliable narrator

Humans are infamously inaccurate narrators, when asked to recall events, regardless of our confidence level in our memory, our recollection is almost always inaccurate. We tend to see our memory as a video that we can go back, rewind and nothing has changed, untouched and unbiased - The truth is we have numerous biases that influence our memory, and every time we recall a memory, we change it just a bit.

Studies on memory reliability have shown time and time again that we are good at remembering the big events; for example where you were when you heard the news about 9/11, however the small details, what you were wearing, what else you did that day, are either forgotten or remembered incorrectly. The idea that memories are often inaccurate can be a disconcerting idea if you’re not familiar with it, however lapses in memory are more common than you think and our brain can go so far as to entirely fabricate memories (known as false memories). An interesting thing about false memories is that even when we've been shown that they're wrong (for example remembering you were at an event but a photo proving you weren’t) you still have that false memory, you know its not true, but that doesn’t make it go away.

Changing your mind

A good skeptic doesn't go after people’s opinions, if you prefer pineapple on pizza and we don't, we're not going to try to change your mind. However, if you claim something falsifiable, for example, that pineapple pizza will double your testosterone level, then that’s where we start stepping in and have a look at the evidence.

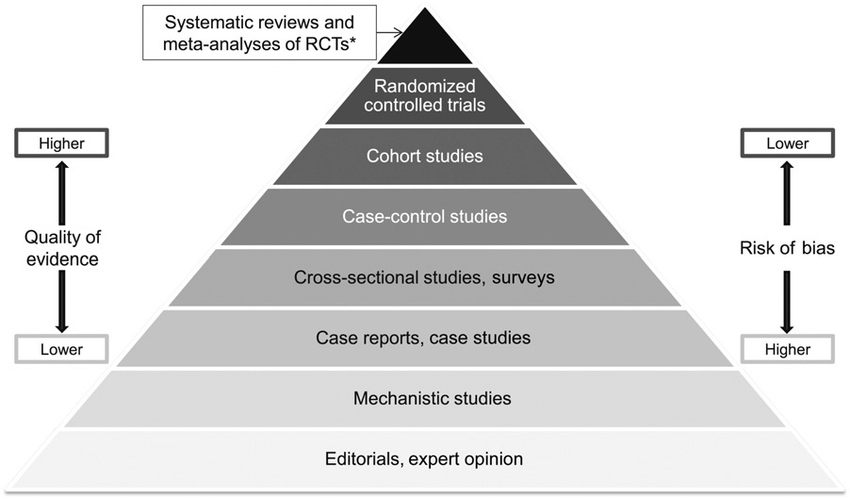

Skeptics can come across as that annoying kid who always asks for evidence, but it's not without reason; if a claim is made it needs to be backed up with evidence. Anyone can make a claim, but a claim with evidence behind it does and should be given far greater weight than one without evidence. Knowing the hierarchy of evidence can help you weigh a claim accuracy - With anecdotal stories (personal stories) at the bottom and systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top.

While anecdotal evidence often sounds compelling and is often used as a sales tactic (“I felt so much happier after eating x food for a week” for example) they aren’t reliable, and when measured in a laboratory setting it is consistently found that anecdotal reporting is the least reliable and most prone to human bias and error.

A common example is someone who began taking a supplement and started losing weight, it is easy to understand why they would attribute this weight loss to supplement x, but correlation does not equal causation. Is it the supplement actually causing this weight loss? Or is it the activities that often accompany habit changes: exercising more, paying more attention to their health, improving their diet etc that are actually causing the changes. The lack of reliability in self-reported data is why the two fundamentals of scientific studies, a treatment vs control group, and objective researchers are so important - They let us see if a treatment is actually working by comparing those doing a treatment with those who aren’t.

At the top of the hierarchy of evidence are systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This type of research doesn’t look at single studies (which reduces the chance of biased data), but is rather a painstaking summary of all the available primary research in response to a research question (with often thousands of studies summarised) - If over time enough systematic reviews and meta-analyses are completed showing the same result a consensus is formed

*Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of observational studies and mechanistic studies are also possible. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

The scientific method

At the basis of the scientific method (and skepticism by default) is methodological naturalism, every material effect has a material cause, no magic or miracles randomly changing the laws of nature. A core concept is that science doesn’t attempt to prove things right, but rather to prove things wrong, science as a whole continually moves forward by proving old research incorrect and replacing it with new, better research. Science is an endless process, we build models that are capable not only of explanation but of prediction, and then we test those models, modifying and rejecting them as necessary. The often used argument ‘science has been wrong before so why should we trust it now’ is a poor one, as the only reason we knew the science to be incorrect is because it was replaced by better evidence which is the scientific process in action.

The longer a scientific notion survives, and the more independent lines of evidence that lead us to the same conclusion, the higher our confidence in that idea. - Dr. Steven Novella

Scientists don’t accept miracles or magic as an argument for something because these create unfalsifiable claims, which are a big no-no in science because you can’t disprove them. An example given by Carl Sagan is of the ‘invisible dragon in the garage’, where he tells you that he has an invisible dragon in his garage. You look in the garage but see no dragon. “Oh I forgot to mention the dragon is invisible”. You decide to put flour on the floor to see its footsteps. “The dragon floats”. You go to use an infrared gun to see the dragons fire. “Oh, the dragons fire is heatless”. You decide to spray paint the dragon to see it. “Oh, I forgot to mention the dragon is incorporeal”. While an over the top example, these kinds of unfalsifiable claims are still made and highlights the issues of unfalsifiable claims.

Claims that cannot be tested, assertions immune to disproof are veridically worthless, whatever value they may have in inspiring us or in exciting our sense of wonder. What I'm asking you to do comes down to believing, in the absence of evidence, on my say-so. - Carl Sagan

Skepticism in action

It’s all well and good to talk about skepticism, but what does applying these skills look like in the real world? A recent and ongoing skeptical challenge is the reporting around COVID-19, with serious misinformation being spread around the internet by armchair experts. If you’re not someone with a scientific background, or are unsure of where to look for reliable information it can be a scary and confusing time which makes separating fact from fiction very difficult.

While there is no one right way to skeptically analyse a claim, if you follow a general checklist you are better able to spot misinformation and pseudoscientific claims.

The skeptical checklist

1. The smell test

Does the claim run contrary to things you have heard previously (This does not necessarily mean the claim is wrong, but requires a closer inspection).

Is the claim going against established scientific principles?

2. The source

Who is making the claim?

Do they have any legitimate credentials?

Do they have legitimate credentials but have a track record of making claims contrary to evidence?

Is the claim made by someone with a history of posting unreliable information (see Alex Jones)

Is this a primary source, secondary source or other?

— If the source is a study, what journal is it coming from? (Certain journals hold far more credibility than others due to more rigorous peer reviewing processes)

3. The claim

Is the claim contrary to the scientific consensus?

Does the claim have logical fallacies in it? (I.e. appeal to emotion)

Is someone making money off making this assertion (For example selling supplements to ‘boost your immune system’)

Does the claim appear motivated by personal or political bias?

Does the scientific consensus support the claim?

If the claim passes through the skeptical checklist unscathed, it is likely that the claim is reliable, however, you must remain open to changing that stance if new information comes to light.

Take home points

Your perception of reality may seem objective and true, but your inherent human biases means you never see things as they actually are - You just need to be aware of your biases

Knowing about cognitive biases doesn’t make you immune to them, just more aware of them and better able to adjust your behaviour to suit

Good critical thinking skills take practice but are an essential skill to guard against misinformation

Science is an endless process; it will never be ‘done’, rather it is constantly working to improve upon itself and what we know